Tired all the time? Chronic pain? Fibromyalgia? Stressed? Below Ingebjørg Midsem Dahl looks at what pacing can do for your health …

Do you find that fatigue and pain stop you from doing the things you want to do? Pacing is a method that can help you lead a richer life, without worsening your symptoms. It’s usually recommended in illnesses that give fatigue and pain, such as autoimmune disease and ME, but it can also be used to treat and prevent burn-out. Even healthy people can get more out of their energy levels by pacing themselves. Pacing is essentially a method of self-regulation. It’s based on the principle that the body sends out signals, both when it wants less activity, and when it wants more activity. When we learn to read these signs and act upon them, we can find an activity level which gives optimum health. It should be noted, that poor self-regulation is not the cause of chronic illnesses. However, even people who previously were good at self-regulation typically find that they need new and more advanced techniques when they get ill, because their bodies’ needs have changed. In the case of burn-out, lack of self-regulation skills may be the main cause of the problem, in which case better self-regulation skills will help you get back into balance.

What is Pacing?

Pacing involves splitting activities into smaller bits, which either don’t cause an increase in symptoms, or cause as small a flare-up as possible. It also means alternating activity and rest, to recharge the batteries regularly. Switching between different activities, which require different body parts to avoid wearing out the same body part all the time, is another important tool. Throughout this process, you listen to your body to make sure your body gets both the activity, and the rest it needs.

How Pacing is Done

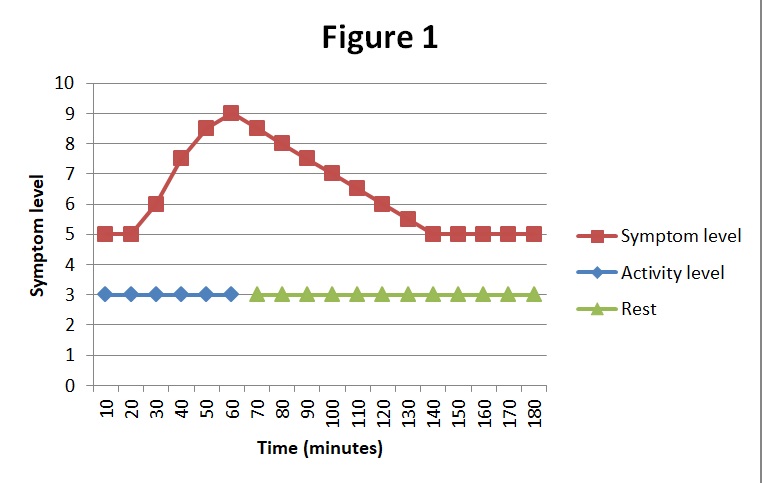

How then, do you do this in practice? In many illnesses which cause low energy levels or pain, symptoms vary depending on your activity level. You may find that you don’t feel too bad at the start of your activity, but after a while you reach your limit, and symptoms will then increase, until you’re forced to stop. This is what is shown in figure 1, where a person keeps going for an hour, which leads to a huge increase in symptoms. The person then has to rest for a long time, to bring the symptoms down again. This is a good example of what happens when you don’t pace yourself. This pattern exists in several sizes. It can be observed on a small scale throughout the day, doing a lot one hour and having to rest the next. It can also be seen from day to day or week to week. You may do a lot on a good day, and then feel worse for several days afterwards because of it, or have a few good weeks followed by some bad weeks.

In either case, the strong flare-ups of symptoms will cause a lot of suffering. Figure 2 shows what happens when pacing. In this case, the person breaks of the activity after half an hour, when the symptom level has only risen by one notch. The symptoms go away much more quickly, and soon the person can handle another round of 30 minutes of activity, and still only get a small change in their symptom level. This reduces suffering significantly. The shorter rest breaks also help reduce feelings of boredom and hopelessness.

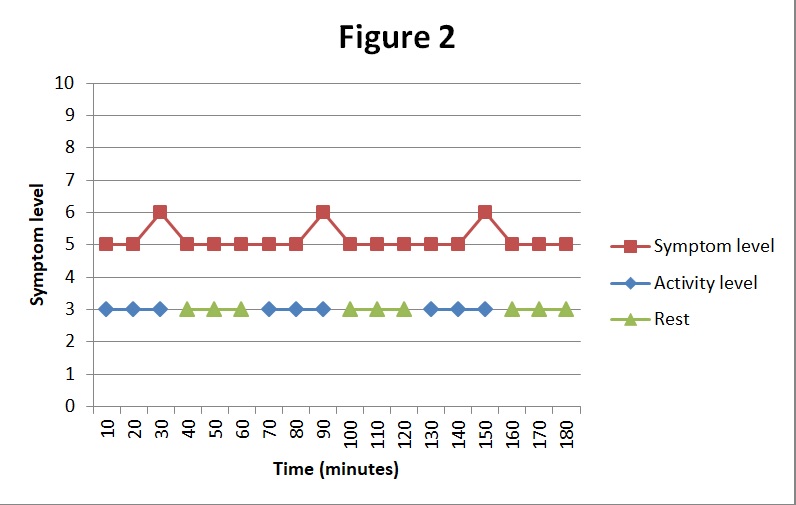

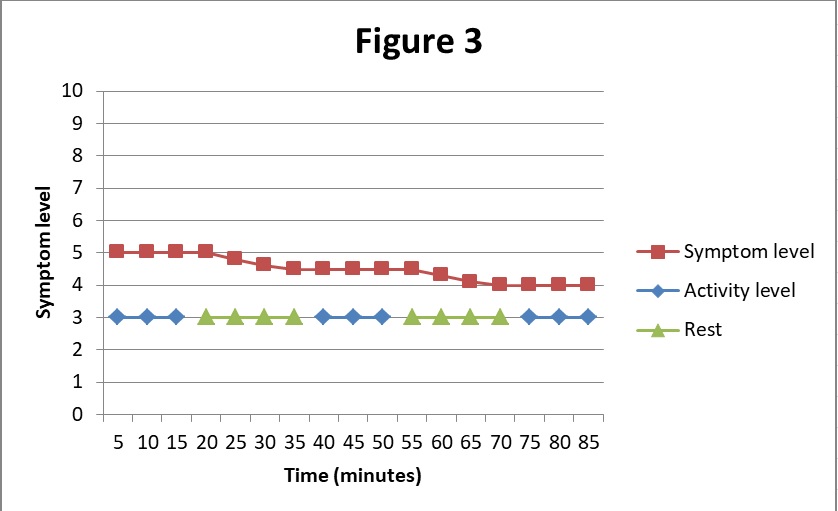

Figure 3 shows an even more thorough approach to pacing. In this case, the person stops before there is any change in symptom level at all. Both of these approaches to pacing can lead to gradual improvement of background symptom level over time. In some illnesses such as ME, the more thorough approach may also be more effective. You need to experiment to find out what suits you best, and consult with a healthcare professional, if in doubt.

How Do You Achieve Pacing in Real Life?

There are two main approaches. The first is to learn to recognise an increase in symptoms, as a warning sign. As soon as you notice an increase in symptoms, break off and have a rest. This approach can work very well when you’re alone, but may be difficult when you are doing things with other people. It’s also very easy to get so absorbed in things that you don’t notice the increase in symptoms until it’s gone rather too far. In this case the second approach may be more effective. In the second approach, you plan in advance how long you are going to stay at the activity. You can even use a timer to remind yourself that it’s time to stop.

Know How Much Energy You Have

Base your plans on what you already know about your activity level. If, for instance, you usually start to get symptoms after half an hour, you can plan to switch to another activity after twenty minutes. Giving yourself a few minutes of safety margin is always a good idea, because life has a fantastic tendency to throw unexpected events at us. If you knock over a glass of milk during a meal, it’s nice to have the extra energy to mop it up. The only way to plan for that type of event is to make sure you have a bit of extra energy left over. When planning, take into account that some activities are physical, others are mental and yet others are social, and some may be all three at the same time. Activities also use different body parts.

Switch Activities

If you switch between different types of activity, you can usually keep going for longer before you need to rest. For instance, you might empty the dishwasher and then sit down and read for a few minutes. You can then go for a walk, before lying down and listening to an audio book. After that, you can lie down and have a proper rest before you do another round of the same or other activities. You’ll need to experiment to find out how long you can go on, and which activities you can do in a row. Once you find the combination that works best for you, you’ll likely discover that you’ll feel less ill and get more done.

Rest

I’ve already mentioned rest several times in this article, but what exactly does rest mean? That depends on your state of health. For healthy people, light activity usually counts as rest, since healthy people can rest one part of the body while using another. For instance, they can rest their legs while watching TV, and rest their heads while going for a walk. When you’re ill, this switching method usually enables you to get more out of your energy reserves, but many need total rest in order to properly recharge their batteries. Total rest means lying down in a quiet room, with either soft lights or an eye mask. Some people may be able to rest sitting up.

Know How Much Rest You Need

Planned, short and regular rests help keep symptoms to a minimum because your batteries are recharged regularly throughout the day. Try taking five or ten minutes of rest every hour. This is better than going on for several hours until you feel bad, and then having to rest to recover. How much rest you need, will obviously depend on your state of health. Some people will need to add longer rests in addition to the short ones. Those who are very severely ill may need 50 minutes of rest and ten minutes of activity per hour. You’ll need to experiment to find a balance which keeps symptoms caused by over-activity down to a minimum, while not provoking symptoms of under activity, such as stiffness or loss of muscle mass.

Since resting is not fun, many people find that the risk of over-activity is greater than the risk of under activity. Be aware, though, that spending most of your energy on light mental activity to prevent boredom may sometimes spend the energy which could have been used for some small, physical activities. A friend of mine found that doing a bit less mentally and resting a bit more enabled her to do more physically. With time, the increase in rest and the improvement of activity balance led to noticeable improvement in her health. When that’s said, it’s important to keep rest breaks pleasurable, to maximise quality of life. Those who can enjoy light activity during their rest breaks, without adversely affecting their health, should do so. When this is not possible, finding a good balance between light activity, more strenuous activity and total rest, will still make your day as pleasant and productive as possible.

Deep Relaxation

The most efficient and restorative type of rest is deep relaxation. Half an hour deep relaxation has been shown to be just as effective as several hours of sleep. It also helps reduce pain. It can bring some much needed wellbeing to a suffering body. Relaxation also helps to reduce boredom during rest breaks, because it gives you something to do. Using relaxation techniques during at least one of your daily rest breaks can help you get the maximum benefit out of resting. If you are lucky, you may even find that you can get away with a bit less rest. The easiest ways to learn relaxation from home is to download a free app on your phone or get a CD. The free app “Insight Timer” is useful because it has several thousand free sessions in a number of different languages. If you prefer a CD, I can recommend the one that comes with the book “Mindfulness for Health: a practical guide to relieving pain, reducing stress and restoring well-being” by Vidyamala Burch and Danny Penman. This book is an excellent introduction, and because Vidyamala Burch has chronic pain herself, it’s both friendly and non-judgemental.

Structure and Planning

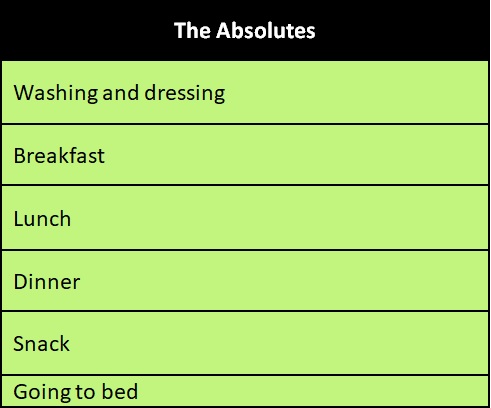

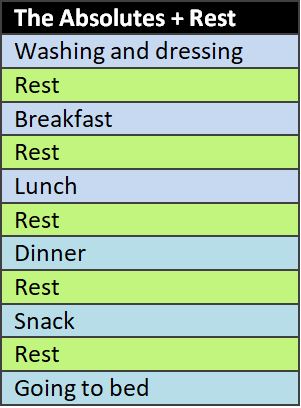

Pacing becomes considerably easier if you combine it with planning strategies and have some structure to your day. Some professionals advocate strict, detailed schedules which tell you exactly what to do at a particular time of day. Although useful for some, many find that an approach which allows for a degree of flexibility is easier to combine with life. Thinking of your day in terms of blocks of activity and rest can be very useful. In this approach, activities such as meals and personal care are considered absolutes. You plan the rest of the day around them. You can move the absolutes but you can’t drop them.

Around these absolutes, you plan a number of rest breaks which allow you to get through the day with the least amount of discomfort and no crashes.

Plan Rest Breaks

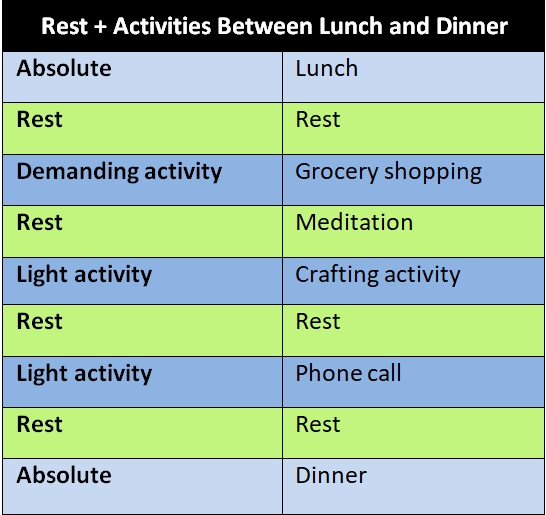

Between these rest breaks and meals, you fit in your activities. Again, you plan an amount of activity which does not cause flare-ups of symptoms. The activities have a length and distribution which allow you to get through the day. This means that somebody who is working part-time will have an entirely different framework for their day than somebody who is bedbound. A demanding activity for the first person might be 6 hours of work, and a demanding activity for the second person might be having their hair washed in bed. Let’s say you can cope with two light activities between breakfast and lunch, and one demanding and two light activities between lunch and dinner. You can then plan suitable activities to fill these blocks. These could be a practical activity around the house, followed by mental activity like reading. The demanding activity could be grocery shopping, followed by a craft activity and a phone call.

Variety Helps

Variation is useful to avoid wearing down particular body parts. Planning for variation is a lot easier when you think in terms of blocks of activity. You can plan different activities every day and still get a sensible distribution fairly easily. There is also room for some flexibility in that you can move the activity periods around. If necessary, you can do the demanding activity in the morning and move the small morning activities to the afternoon. Sometimes you might substitute a demanding activity for two small ones or vice versa. This will keep the total amount of activity stable. What you can’t do is choose a demanding activities instead of a light activity, as this would cause over-activity. You can use the block strategy to plan weekly activities.

Spread Out Your Chores

It’s particularly helpful to spread survival activities out evenly. These would be activities like grocery shopping, laundry and bill paying. If necessary, split them in smaller chunks and spread them out. This way you can do them without flare-ups of symptoms. The reason it’s so helpful to plan survival activities is because it saves you a lot of thinking. If you follow the weekly routine, you know that you will do all the completely necessary things. In the event that something out of the ordinary happens, you can swap things around so that the most necessary things get done anyway. This means that if you have to drop something, you know what didn’t get done. And so you’ll be able to prioritise it next week. When your energy levels are low, it’s nice to be able to do some things on autopilot. One of the most important benefits of this type of forward planning is that it gives you the opportunity to plan some pleasant events in-between the more work related activities.

It’s particularly helpful to spread survival activities out evenly. These would be activities like grocery shopping, laundry and bill paying. If necessary, split them in smaller chunks and spread them out. This way you can do them without flare-ups of symptoms. The reason it’s so helpful to plan survival activities is because it saves you a lot of thinking. If you follow the weekly routine, you know that you will do all the completely necessary things. In the event that something out of the ordinary happens, you can swap things around so that the most necessary things get done anyway. This means that if you have to drop something, you know what didn’t get done. And so you’ll be able to prioritise it next week. When your energy levels are low, it’s nice to be able to do some things on autopilot. One of the most important benefits of this type of forward planning is that it gives you the opportunity to plan some pleasant events in-between the more work related activities.

Pacing Can Improve Your Life

Make sure you get the chance to enjoy yourself a bit every day. This is incredibly important in order to maintain quality of life. That’s the whole point of pacing – improved quality of life.Between these rest breaks and meals, you fit in your activities. Again, you plan an amount of activity which does not cause flare-ups of symptoms. The activities have a length and distribution which allow you to get through the day. This means that somebody who is working part-time will have an entirely different framework for their day than somebody who is bedbound. A demanding activity for the first person might be 6 hours of work. A demanding activity for the second person might be having their hair washed in bed.

Mix Up Light and Demanding Activities

Let’s say you can cope with two light activities between breakfast and lunch, and one demanding and two light activities between lunch and dinner. You can then plan suitable activities to fill these blocks. These could be a practical activity around the house, followed by mental activity like reading. The demanding activity could be grocery shopping, followed by a craft activity and a phone call. Variation is useful to avoid wearing down particular body parts. Planning for variation is a lot easier when you think in terms of blocks of activity. You can plan different activities every day and still get a sensible distribution fairly easily. There is also room for some flexibility in that you can move the activity periods around. If necessary, you can do the demanding activity in the morning and move the small morning activities to the afternoon. Sometimes you might substitute a demanding activity for two small ones or vice versa. This will keep the total amount of activity stable. What you can’t do is choose a demanding activities instead of a light activity, as this would cause overactivity. You can use the block strategy to plan weekly activities.

Greater Stability – the Key to Quality of Life

One of the greatest benefits of pacing is the increased stability it gives. When your health is fluctuating wildly, it’s difficult to plan. So you frequently face the disappointment of having to cancel appointments. When pacing reduces the number of flare-ups of symptoms, you stand far greater chances of actually being able to carry out that café trip you have planned on Thursday. There may still be fluctuations, but they tend to be milder and may not force you to cancel things. Stability enables you to split large projects into smaller bits and build them up in stages. This in turn makes it possible to achieve things you could never have done in one go.

Open University

A friend of mine, who is severely ill, is currently studying for a degree through the Open University. She studies for 20 minutes three times a day. Another friend published a small literary journal for five years by working in similarly short periods. She has also completed a crochet blanket by crocheting only one row of stitches per day. A man I know managed to build a raised flower bed for his and his wife’s garden. He got the shop to cut the planks to the right length and then carried the planks to the car in stages. At home, he left the planks in the car for several days to recover properly before he carried them to the garden in stages. Assembling the flower bed was done little by little over a period of two weeks. This way he managed to complete the project without any harm to his health, which made the whole project a lot more enjoyable.

Pacing Helped Me Publish My Book!

Personally, I dictated a book about pacing whilst bedbound and very severely ill. I dictated most of the book in one minute sessions. I edited it by having it read out loud to me for a few minutes at a time. It took ten years before the book was published, but during this period my health improved very considerably. I was so ill I couldn’t do anything in the normal way, and it would have been very easy to think that I couldn’t achieve anything. Instead, pacing gave me the opportunity to accomplish something while enhancing my health at the same time. This is proof that perfect health is not a necessary part of an enjoyable life. With methods like pacing you can live a rich and fulfilling life in spite of health challenges. Pacing can simply give you your life back.

About the AuthorIngebjørg Midsem Dahl, born 1979, lives in Oslo, Norway. After coming down with ME in early childhood, she has taken a profound interest in coping and management. She has contributed to the newsletters of ME associations in several countries, especially in Norway, Denmark and Great Britain. Her book, Classic Pacing for a Better Life with ME, was published in Norway in 2015, and the English version was published in late 2018.

For more info: www.pacinginfo.eu and www.facebook.com/pacinginfo

© Ingebjørg Midsem Dahl 2018

I had never heard of the term pacing until today-my energy levels in menopause are way lower than before. My husband has noticed signs of tiredness – and suggested rest (readiing a book usualoly but sometimes having a soak in the bath!) but that felt like a band aid or that I was wimping out… but now after reading your article I am inspired to try interspersing the book reading with other activities and see how that goes. (I’m on my feet most of the day- standing at my PC or mixing ingredients… all for lengthy time intervals. I’ve been holding back the book reading as a reward at the day but often I’m over tired that sleep isnt so easy. So your article has given me new ideas on energy management.. so a big thank you.